One challenge that I have observed over many years speaking and writing about professional relationships is the tendency for many people to view networks as binary. The subconscious assumption is that someone is either in your network or not, with little thought given to what happens after the point of connection. A notable real-world example is LinkedIn, where people connect with each other without engaging in conversation and take pride in the growing size of their network.

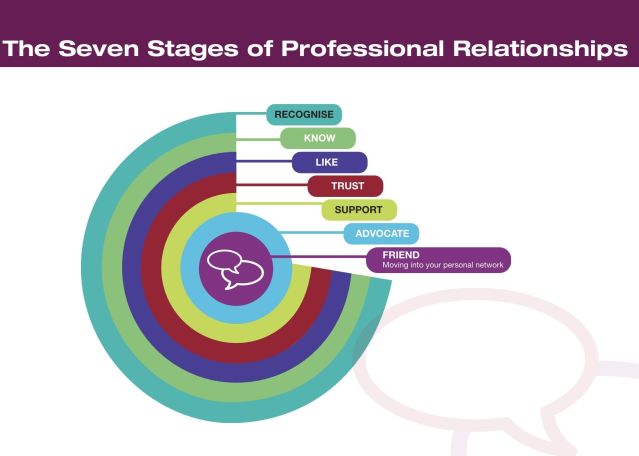

In my 2020 book Connected Leadership, I introduced a simple model of professional relationships, the Seven Stages of Professional Relationships, that has proven to be useful for many of the groups I’ve worked with. It encourages people to examine workplace relationships with an eye to understanding the strength of their existing connections, their blind spots (key relationships that are weaker than ideal) and how to nurture relationships in order to gain support and influence.

Many people rely on instinct and assumption when scoring relationships against the model, trying to understand how other people feel about them. And remember, when building a network to support you in your career or role, it’s far more critical to focus on how others see you than on how you feel about them. There are simple tools to help make the process easier, but individual instinct is a good starting point.

As useful as a simple approach is as a starting point, the challenge arises when you fail to factor in personality differences between people. A trait that may seem obvious in one person might be less clear in someone else, particularly if they are neurodivergent or from a different culture. Without considering personality and cultural variation, it’s easy to misinterpret others’ actions and under- or overestimate the strength of a relationship. Serious use of this model relies on an understanding of differences in personality styles and culture.

How Our Differences Might Impact Each Stage of Relationship

If we look at how others perceive our relationship through the lens of their neurodivergence or cultural differences, we can start to challenge our assumptions.

For example, it might be natural to believe that others know what we do after meeting us several times, but a neurodivergent person may need far more detail than others before really understanding. Someone from a culture that considers it impolite to challenge or query another person (particularly somebody in a more senior role) may show expressions that suggest comprehension despite that not being the case. In some cultures, there may be a signal that appears to be agreement or understanding but is simply a gesture of respect or politeness.

On the other hand, because many neurodivergent people don’t send the social cues that typically indicate liking, and not all cultures signal affinity for others equally openly, we may think that people don’t like us when they do.

Neurodivergent Cues and Clues

As Dr. Samantha Hiew, author of Tip of the ADHD Iceberg, explains, neurodivergent individuals—whether they’re autistic, have ADHD or some other condition—may show differing behavioural responses depending on context, and the responses don’t always align with neurotypical expectations. When interpreting professional relationships through the Seven Stages framework, it’s important not to assume that familiar cues such as eye contact, facial recognition, or verbal affirmation will always be present—or even relevant.

At earlier stages, someone who is neurodivergent may recall what you do but not recognise you visually, or may appear reserved in their acknowledgement. At the “Know” stage, their understanding might centre on practical roles and clearly defined tasks, rather than on inferred status or broader organisational positioning.

In later stages, like Support, Advocacy, or Friendship, warmth or loyalty may be expressed through reliable action, task-based support, or structured communication rather than overt praise or informal gestures. Such behaviours are not signs of disconnection or disinterest but rather reflect different relational styles that can be easily overlooked or misread.

Just as we can’t easily judge relationship strength on a set of generic cues, it’s important not to fall into the trap of assuming that all neurodivergent people will act the same way. The key is not to apply a fixed template but to remain open to the many ways that trust, respect, and connection can be expressed—and to check our assumptions when expected cues aren’t there.

Cross Cultural Perspectives

The same can be true of different cultures. Adrienne Gibson, director of Genesis Global Consulting and a leading cultural expert who has worked with companies in more than a hundred countries, stresses the huge diversity of social interaction and behaviour across different cultures. What we expect as the norm in one culture can present itself in a vastly different way elsewhere.

This is particularly true where hierarchies are more powerful or gender roles more ingrained in the culture. People might recognise and know you but be less likely to greet you informally if it is inappropriate. Visible status will be more important in some cultures than in others and may dictate how someone interprets your role and relevance.

It can become easy to be confused by signals and social cues that have completely different meanings across the world. In India, people will shake their head in agreement with you, which can be taken as disapproval or disagreement in Western cultures. In one culture, it might be expected to show your hospitality by sharing food and inviting people into your home, while in others that honour would be reserved for closer relationships.

How to Navigate Meaningful Relationships with Different Personality Types

Applying a one-size-fits-all lens to our expectations of professional relationships can be problematic. We may push people away when they feel drawn to us, or we may be too close too quickly. Expanding our understanding of what connection looks like means asking ourselves how each person with whom we engage prefers to connect or demonstrate their trust in us.

To approach relationships respectfully, change the questions you ask yourself. Instead of seeking to understand whether someone likes you, ask how they would express liking or trust. Explore what trust would look like for that person or how they might show support. Sometimes the signs that somebody likes or trusts you might not be in a smile or a relaxed conversation but in positive responses to requests, including you in their work and decisions, or a willingness to introduce you to people in their network.

Don’t be frightened to ask people how they like to interact and what makes it easier for them to build relationships, particularly if you openly acknowledge your differences. By doing so, you’ll demonstrate a willingness to connect on their terms and respect for their perspective.

It will also pay to slow things down. Don’t expect relationships to all progress at the same speed. Some people need longer to feel comfortable with you, particularly if you have less in common.